HORRIFYING AND DELIGHTFUL

An interview with Giulia Bencivenga about their new chapbook, AMASSING LIFE, available now from Dead Mall Press.

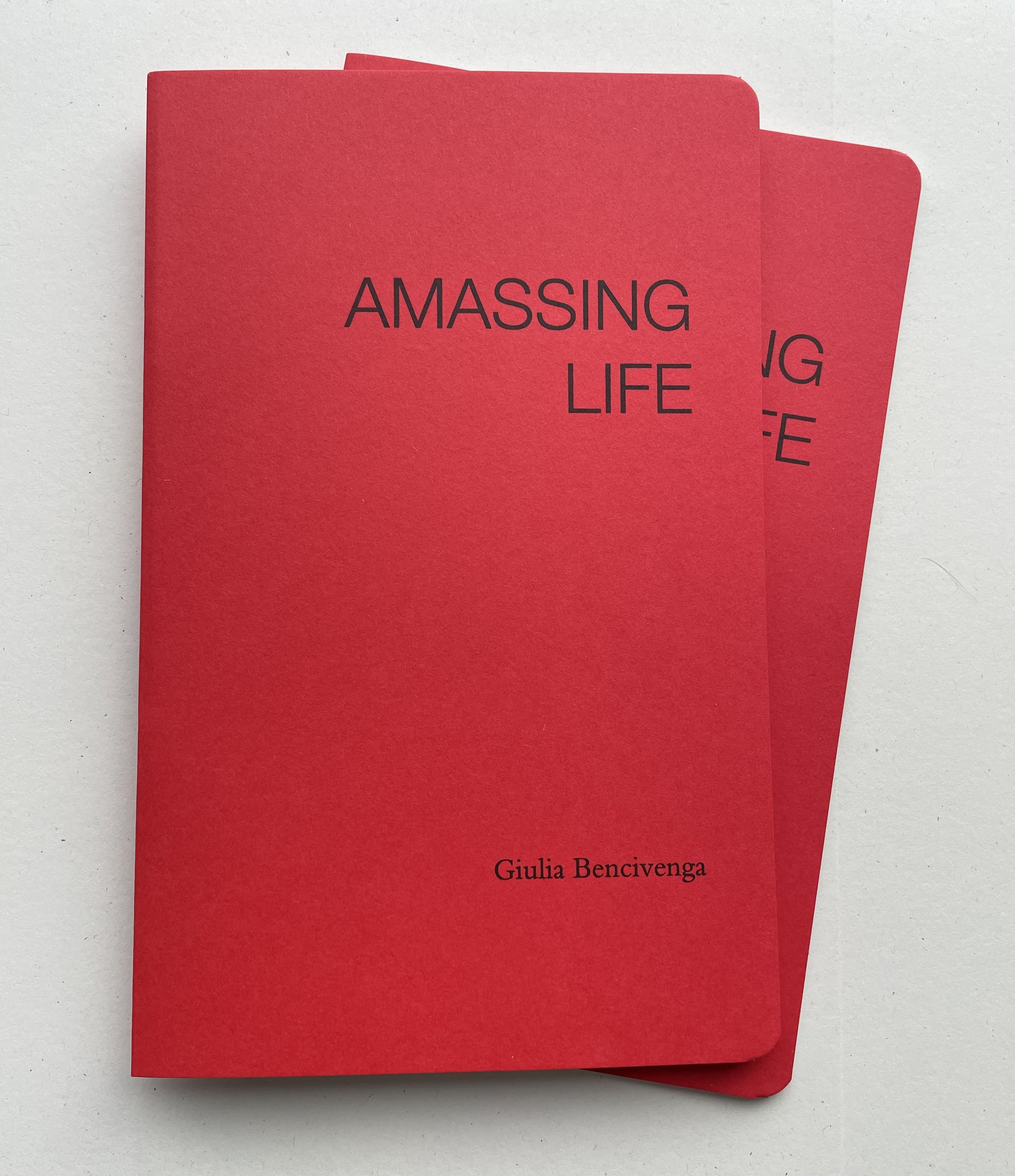

On October 13 of this year, we released a new chapbook by poet Giulia Bencivenga. It is thirty pages long with a bright red cover and dark blue end paper, and you can order a copy here. About the poems beneath that cover, I had this to say:

Amassing Life is both vibrant and enigmatic. The poems disarm you with naturalness, candor, and insight, and yet their center of gravity also uproots you, pulling away toward something unknown. And there, life begins to fill with itself to a point of disorientation and dread—should you panic or fall in love? Vulgar hearts, seagull fractals, grim roses, the taste of money. You can hear a voice that folds itself inside out, pivoting abruptly, from the antic to the seer, shifting like clouds or shafts of light, knowing even the flowers have ideas. In other words, these are poems about living to die and dying to be alive. They reach from the hidden core of the soul out to the splayed nerve-endings and furthest reaches of the skin, and on outward into some indefinable zone of thinking and feeling. Read this and let the blood flow.

Recently, Giulia and I discussed the book via email, and you can read the conversation below.

Also, mark your calendar for an online reading with Giulia and DMP author Isaac Pickell on Wednesday, November 6th, at 7pm EST (4pm PST). More info to come!

Dead Mall Press: Hey, Giulia! Thanks for agreeing to this interview. For those who may be unfamiliar with your work, could you tell us a bit about yourself and your writing?

Giulia Bencivenga: Hi :-) I’m a failed philosopher, an immigrant, and a sickly anarchist, as such my work typically revolves around the indeterminacy of identity, health, sex. My hope is that the poems I write will chip away at the world as it is because, as Lana Del Rey says, “I can’t survive if this is all that’s real.”

People have commented on a “body horror” aspect of my poems, but I have searched for this in my work and not found it. I think having a body is a horrifying and delightful experience and I enjoy exploring all facets of embodiment. I think many just aren’t made aware of the mechanization of their bodies the way I have been made to through the breakdown of various systems, and that can be scary for people. But I feel a sense of pride in my little ruptures.

DMP: So how did this chapbook, Amassing Life, come about? What was the process of writing it like?

GB: My books always come out of some emotional necessity. I had this resounding feeling like I was on the verge of collapse and I needed to document it. In many ways, the collapse had already happened and I was just documenting the fallout in my mind. Fear sets in once one knows there are things to be afraid of, and the fear here was that I wouldn’t feel this free forever. There is something so vibrant about watching yourself shatter, it makes all parts of your mind legible. But despite my writing being fiercely personal, I don’t consider it confessional. I am not trying to absolve myself of shame on my little stage, I wish only to display it in a shadowbox and say, “This is important, too.” Because, as Deleuze reminds us, fantasy is a social phenomenon. And isn’t shame the ultimate fantasy—that one might be judged, that one might be watched? How special that would be.

DMP: The book feels like one big poem. There are no titles, just divisions from page to page, and they all seem to belong to the same mode. It might not really apply here, but what is one of your favorite poems (or sections) in the book and why? How do you see it relating to the rest of the book?

GB: Amassing Life actually did start off as a six page poem, but I noticed that the stanzas needed space to breathe because there was a heaviness to them. So I started playing with how they could show up on the page, together or alone. Every book I put out has its own cadence, its own internal contradictions and logic, and is meant to be read all in one go. And every book speaks from a different part of me, and once I inhabit that emotional space it’s hard for me to find my way out. I didn’t want to leave Amassing Life behind, it was so fun to work on. There’s a ferality in this work that I don’t get to tap into often because of polite society. And so I just kept writing and writing and writing until you, Matt, eventually had to tell me that I no longer had a chapbook on my hands, then I reluctantly stopped.

Some of my favorite parts of the book:

Ah, the search for simplicity left my pockets filled with sand

Plummeting deeper and deeper to the top of the lookout point

I like these lines because they are true.

A facet of the soul is the soul turned against itself

Face up and outwards always— alert

These are a good reminder that to categorize is to create a fissure, that differentiations are necessary politically but can take a spiritual toll. I am often searching for the thing that connects me to other people, but thinking that way in itself is alienating. Better to think of oneself as a stream, a floating orb, or a soul part of the spirit.

There is nothing that isn’t everywhere else

Petals, rich and velvety, fall from the sky

And into my gaping mouth

I am laughing with my mother and father

We are all laughing

Again, I return to substance. Again, I love the idea of people laughing.

DMP: You just had a full-length book published this summer with Dirt Child Press called Comorbidity (or the Reckoning). With these two appearing in such quick succession, do you see them in conversation in any way? And how would you describe that conversation if it exists?

GB: They are in conversation the way sisters communicate, through a hallway of fun mirrors. They have the same parents but different ways of going about getting what they need to survive in the world. In many ways I feel like Amassing is more of a continuation of Giulia Bencivenga Is a Maniac than Comorbidity.

DMP: Who are some of the poets whose work has been important to you? What do you think they have given your own work?

GB: When I was little I would memorize lines from Dante. I loved the Divine Comedy, how petty and romantic one could be all at once. Besides that, Rosmarie Waldrop helped me understand the limits of language, Laura Riding helped me understand the limits of a concept, and Alejandra Pizarnik helped me understand the limits of life. Alice Notley has also been instrumental to me, I am fascinated by her voice—how it has such a breadth of scope but always sounds distinctively hers.

DMP: To close things out, what do you hope that readers take away from reading this book? Or what kind of energy and/or vision do you hope it puts into the world of its readers?

GB: I hope my poems tap into the part of you that remains untethered to reality, the part that loves freely and easily. God knows we need that sort of exaltation.

Author Bio:

Giulia Bencivenga is alive.